Físicos de Columbia ven ondas de luz moviéndose a través del metal

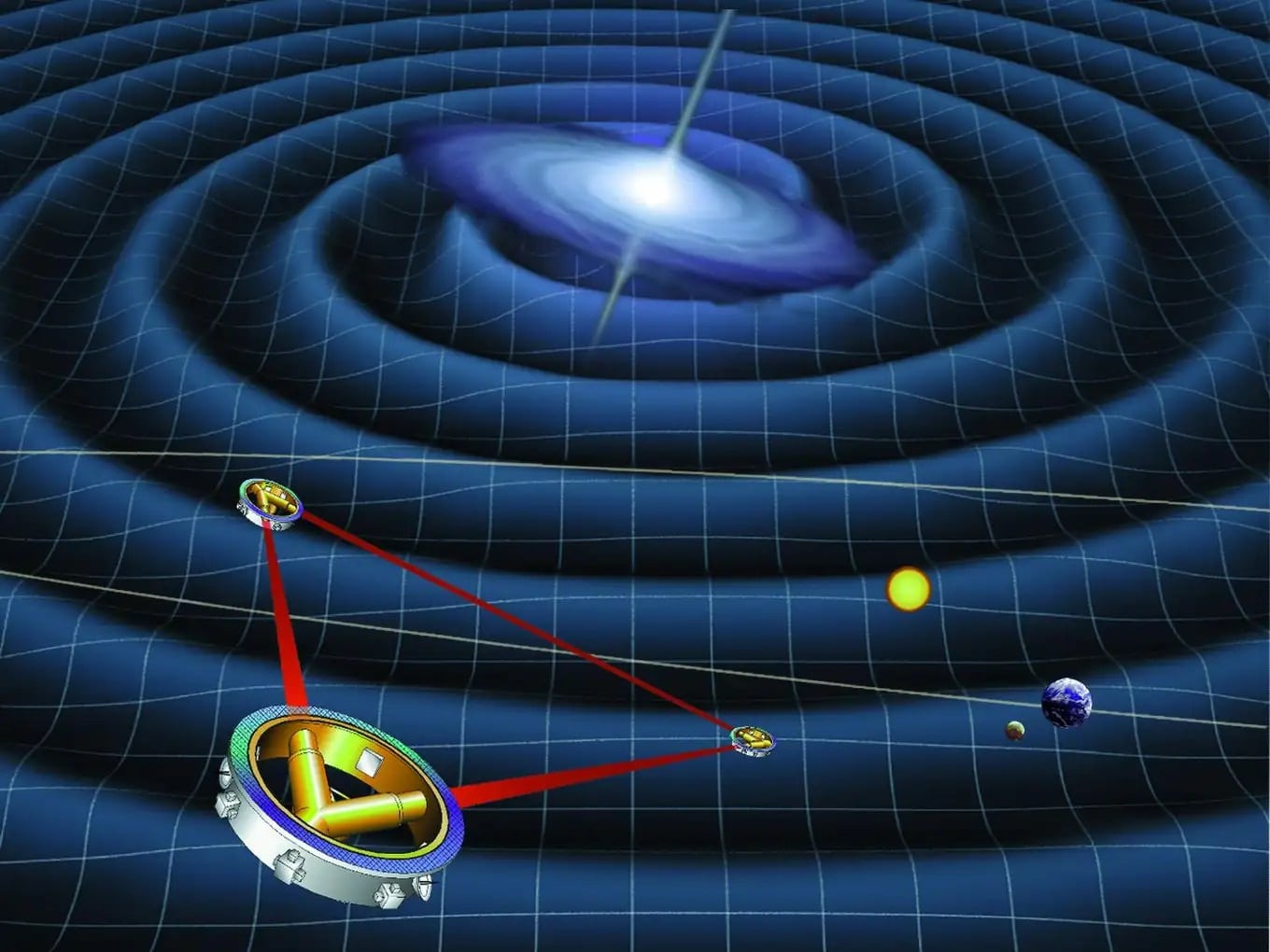

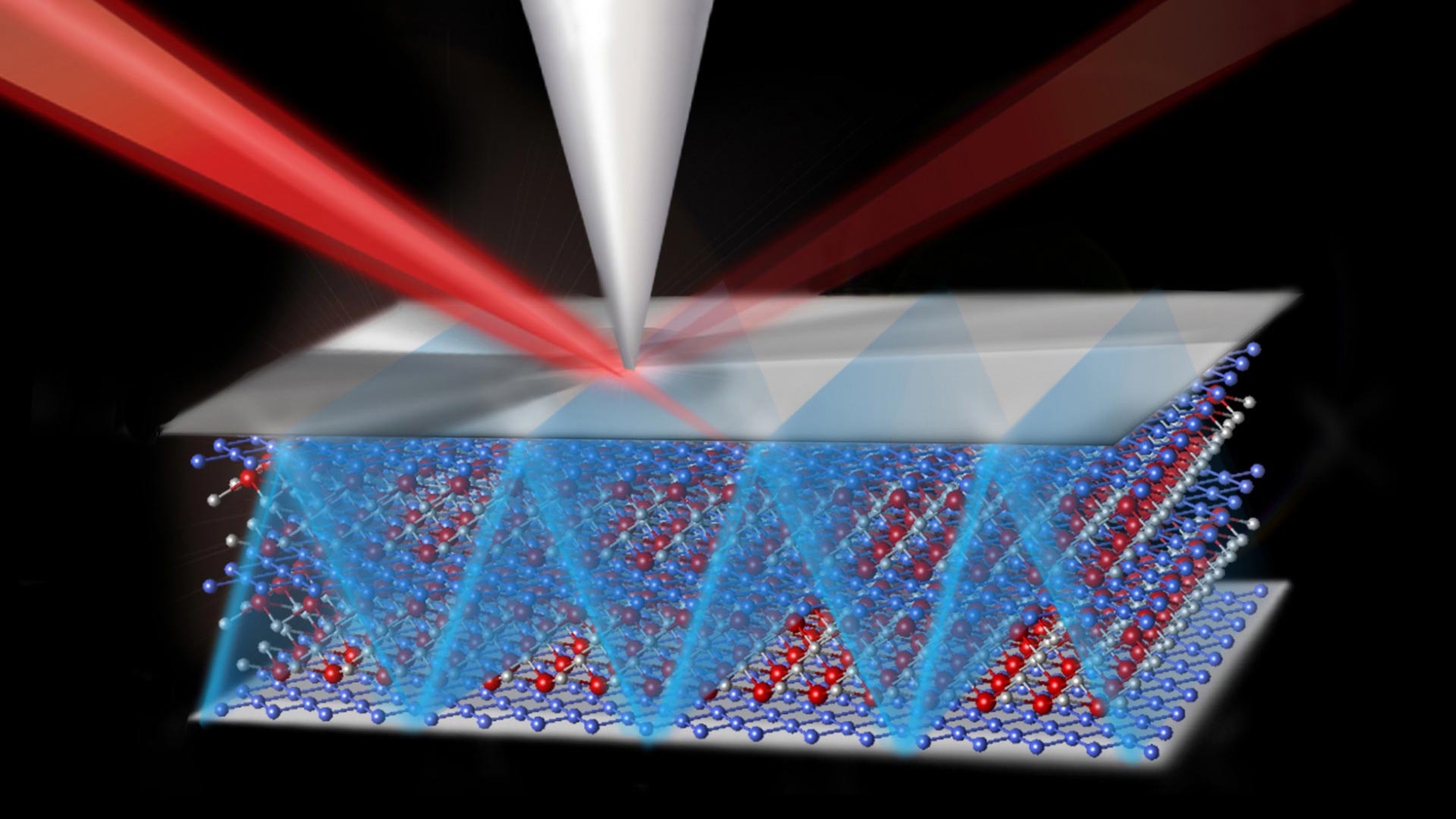

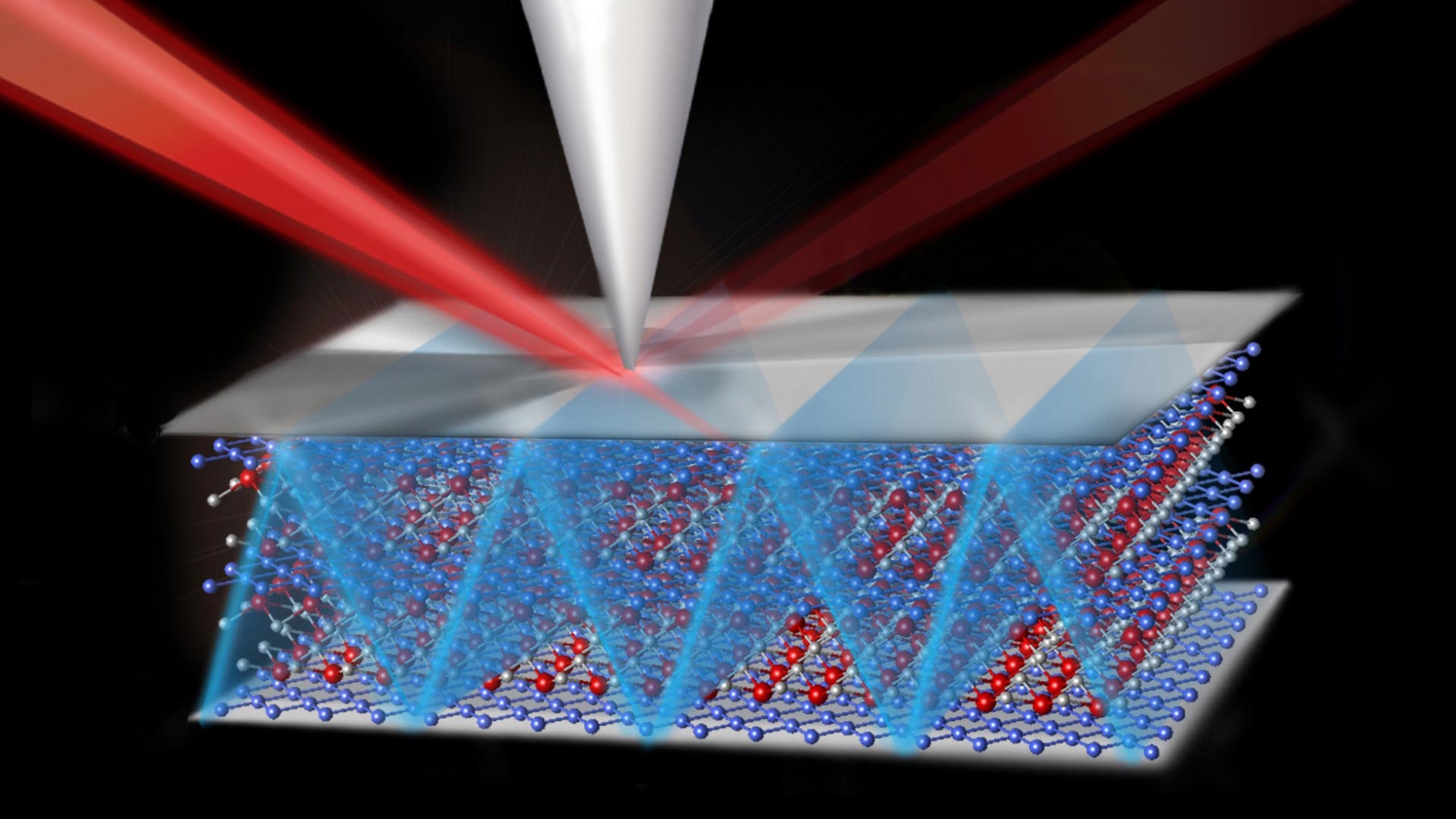

Conducción de la luz en un metal: se observan guías de ondas en un semimetal conocido como ZrSiSe. Crédito: Nicoletta Barolini, Universidad de Columbia

Una nueva investigación encuentra evidencia de guía de ondas en material cuántico único. Estos resultados van en contra de las expectativas sobre cómo los metales conducen la luz y pueden llevar la imagen más allá de los límites de la difracción óptica.

Percibimos los metales como brillantes cuando los encontramos en nuestra vida diaria. Esto se debe a que los materiales metálicos comunes reflejan las longitudes de onda de la luz visible y, por lo tanto, rebotan la luz que los golpea. Aunque los metales son muy adecuados para conducir la electricidad y el calor, generalmente no se consideran un medio para conducir la luz.

Sin embargo, los científicos encuentran cada vez más ejemplos que desafían las expectativas de cómo deberían comportarse las cosas en el floreciente campo de los materiales cuánticos. Una nueva investigación describe un metal capaz de conducir la luz a través de él. Dirigido por un equipo de investigadores dirigido por Dmitri Basov, profesor de física de Higgins en[{» attribute=»»>Columbia University, the study was published in Science Advances on October 26. “These results defy our daily experiences and common conceptions,” said Basov.

“Using hyperbolic plasmons, we could resolve features less than 100 nanometers using infrared light that’s hundreds of times longer.”

— Yinming Shao

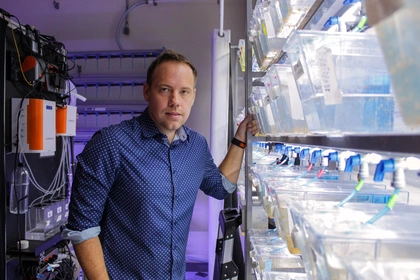

The work was led by Yinming Shao, now a postdoc at Columbia who transferred as a PhD student when Basov moved his lab from the University of California San Diego (UCSD) to New York in 2016. While working with the Basov group, Shao has been exploring the optical properties of a semimetal material known as ZrSiSe. In 2020 in Nature Physics, Shao and his colleagues showed that ZrSiSe shares electronic similarities with graphene, the first so-called Dirac material discovered in 2004. However, ZrSiSe has enhanced electronic correlations that are rare for Dirac semimetals.

Whereas graphene is a single, atom-thin layer of carbon, ZrSiSe is a three-dimensional metallic crystal made up of layers that behave differently in the in-plane and out-of-plane directions. This is a property known as anisotropy.

“We want to use optical waveguide modes, like we’ve found in this material and hope to find in others, as reporters of interesting new physics.”

— Dmitri Basov

“It’s sort of like a sandwich: one layer acts like a metal while the next layer acts like an insulator,” explained Shao. “When that happens, light starts to interact unusually with the metal at certain frequencies. Instead of just bouncing off, it can travel inside the material in a zig-zag pattern, which we call hyperbolic propagation.”

In their current work, Shao and his collaborators at Columbia and UCSD observed such zig-zag movement of light, so-called hyperbolic waveguide modes, through ZrSiSe samples of varying thicknesses. Such waveguides can guide light through a material. Here they result from photons of light mixing with electron oscillations to create hybrid quasiparticles called plasmons.

Although the conditions to generate plasmons that can propagate hyperbolically are met in many layered metals, it is the unique range of electron energy levels, called electronic band structure, of ZrSiSe that allowed the team to observe them in this material. Theoretical support to help explain these experimental results came from Andrey Rikhter in Michael Fogler’s group at UCSD, Umberto De Giovannini and Angel Rubio at the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter, and Raquel Queiroz and Andrew Millis at Columbia. (Rubio and Millis are also affiliated with the Simons Foundation’s Flatiron Institute.)

“These results defy our daily experiences and common conceptions.”

— Dmitri Basov

Plasmons can “magnify” features in a sample, allowing researchers to see beyond the diffraction limit of optical microscopes, which cannot otherwise resolve details smaller than the wavelength of light they use. “Using hyperbolic plasmons, we could resolve features less than 100 nanometers using infrared light that’s hundreds of times longer,” said Shao.

Shao said that ZrSiSe can be peeled to different thicknesses, making it an interesting option for nano-optics research that favors ultra-thin materials. However, it’s likely not the only material to be valuable—from here, the group wants to explore others that share similarities with ZrSiSe but might have even more favorable waveguiding properties. That could help researchers develop more efficient optical chips, and better nano-optics approaches to explore fundamental questions about quantum materials.

“We want to use optical waveguide modes, like we’ve found in this material and hope to find in others, as reporters of interesting new physics,” said Basov.

Reference: “Infrared plasmons propagate through a hyperbolic nodal metal” by Yinming Shao, Aaron J. Sternbach, Brian S. Y. Kim, Andrey A. Rikhter, Xinyi Xu, Umberto De Giovannini, Ran Jing, Sang Hoon Chae, Zhiyuan Sun, Seng Huat Lee, Yanglin Zhu, Zhiqiang Mao, James C. Hone, Raquel Queiroz, Andrew J. Millis, P. James Schuck, Angel Rubio, Michael M. Fogler and Dmitri N. Basov, 26 October 2022, Science Advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.add6169

The work was supported by the Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship and Columbia’s Department of Energy-funded Energy Frontier Research Center on Programmable Quantum Materials, which seeks to discover new materials and tools that can reveal new details about fundamental physics.