People living in the north of the country suffer from a lack of medicine and the lack of adequate tests, while humanitarian organizations try to take advantage of the lack of government support and the lack of official information about the disease.

When she doesn't get her medication, Jennifer Ekai feels like something is "eating her from the inside."Mycetoma, a neglected tropical disease, is destroying the lives of an unknown number of residents in Kenya's poorest county, Turkana (north), due to lack of research and funding.

Ekai, 21, was older than that day when, at the age of ten, he was hit by his leg, the same waist, and he was beaten by his riire.

MitCetoma is part of the 25 diseases of 25 diseases that affect millions of people, especially in the tropical regions of the world, and for which the treatment is not long, toxic, not expensive.

"Mycetoma is the neglect of the neglected," Dr. Borna Nioki-Enok of the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDI) tells EFE in Nairobi.

This disease, endemic in countries such as Mexico, Iran, Sudan, Somalia and northern Kenya, comes in two varieties: bacterial and fungal, much more serious.It attacks the tissues, starting from the skin, and when it reaches the bones, the only option is amputation.

Although in principle it does not kill the patients, it destroys their way of life, because those affected are usually from poor communities who depend on their hands and feet for work, such as the nomadic shepherds of Turkana.

Despite this, its global spread is still unknown as there is no mandatory reporting to the authorities in Kenya or in most countries where the disease is found.

This lack of information leaves patients helpless and means that medicines are not part of the national health budget.

According to Neek Chey, “People who are neglected in terms of health care, medicine and other basic needs and people who are neglected in terms of disease, education and other basic needs, as well as people who are sick, these people are neglected in terms of these people and other basic needs, make people and other diseases unfit.

According to official data in 2022, Turka is the poorest of Kenya's 47 counties, with a poverty rate of about 80%.

Diagnosis and treatment

The sun compels you to peek into the referral hospital in Lodwar, the capital of Turkana.Dozens of people from all over the area are waiting for treatment at the one-story center.

Laboratory technician Johi Ekai, 30, examines the young tumor brother, while the sick brother rode to a remote village where they live for 5,000 shillings 8,000 shillings (about 55 euros).

"To get the right treatment, you need the right diagnosis," said Ica, who was run by the Spanish NGO Cirugía en Turkana, which has held an annual medical camp in the area for two decades.

But this is not always certain for residents of remote villages in the arid Turkana savannah, who walk barefoot on acacia tree bark - which can harbor hundreds of agents that cause infection - and who depend on dispensaries with few resources.

"I think he's not a good surgeon," Dr. Francisca explains to Ekai in a video call.

Of the almost 120 patients registered so far by the hospital workers, "some come to the control, we lose others because they never come back, after giving them the medicine for the first time", this Spanish microbiologist explains to EFE.

Treatment is another complication of myocoma.Although surgery may be an option, currently the recommended drug is ITRaconzole, an antibiotic that should be taken as a pill twice a day for a year twice a day for a year twice a day for a year twice a year.

It is impossible, because today only the Spanish are giving them treatment - free of charge - for which the cost of Euros per patient is paid.

Difficulties in treating it mean that while the cure rate for fungal mycetoma can reach 80%, it drops to 35%, according to data from DNDI, which is supporting a clinical trial of a new drug with a simpler dose.

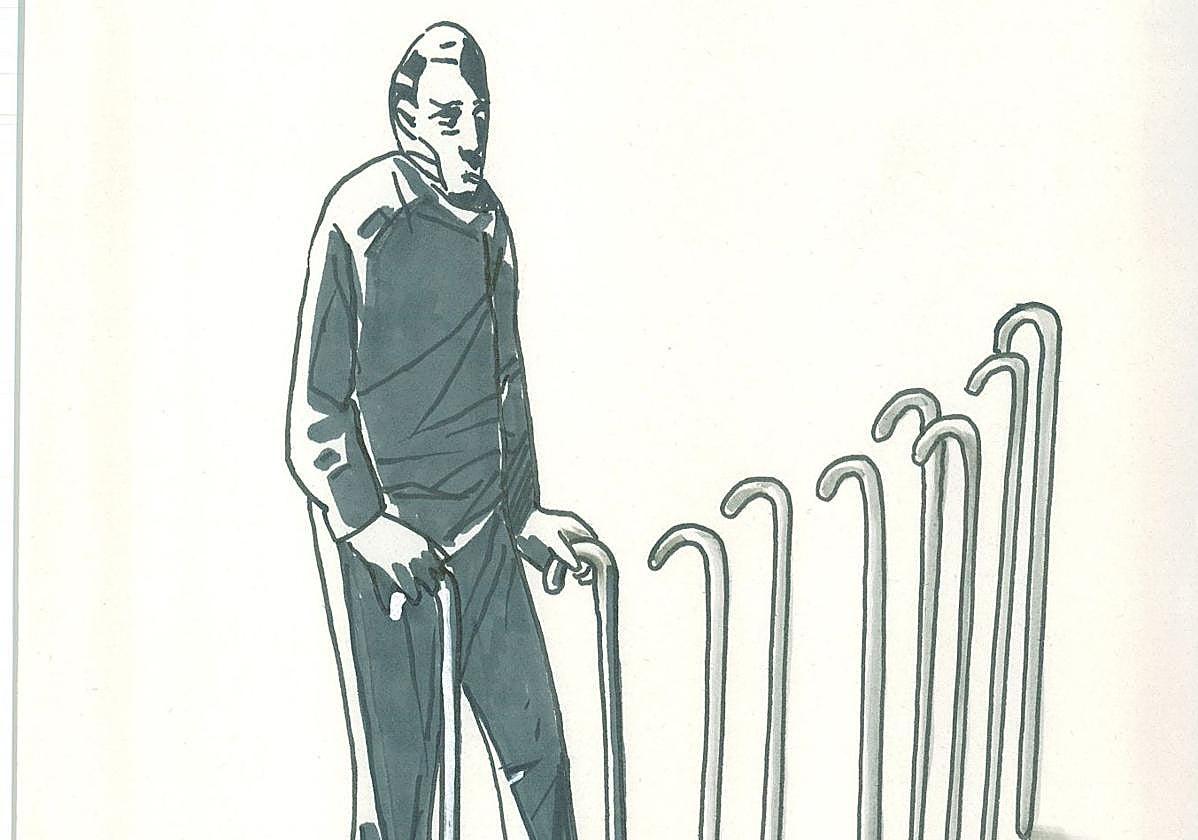

Ekai Akumbaal Losike is well aware of these obstacles.Before the Mycetoma attacked his left leg, the 41-year-old had 400 head of cattle that wandered for days in search of pasture.

Now, he has only ten goats and six donkeys left.The rest were stolen or had to be sold to pay for the medicine he was taking before he got the proper disease, more than a year after the infection.

He doesn't even know if he can pay for her children's school fees, he complained.

Sitting on the screen of his hut, next to the traditional wooden bench that men in Turkana have, Losike insists that he has not missed "a single dose", but when he went to the hospital last October to get more doses, he was told that "he was out of doses".

(with information from EFE)